Karah Sutton author essay

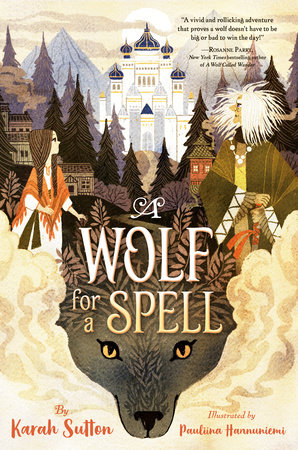

A Wolf for a Spell By Karah Sutton; illustrated by Pauliina Hannuniemi

I’ve always been captivated by fairy tales, and my debut novel, A Wolf for a Spell, is a tribute to the Russian fairy tales I’ve loved all my life. But it’s also a love letter to the natural world. It surprises me how much I enjoyed creating a wild world, when for so long I avoided the wilderness. My favorite passages to write were the descriptions of leaves, clinging brambles, and squelching mud.

Ages eight and nine were my Robin Hood phase. Not only was I determined to learn archery, but I fell deeply in love with the notion of living carefree in the forest. There was a problem, though: I really wasn’t an outdoorsperson. The woods made me uneasy. At summer camp, I stayed near the water and worked on my swimming technique.

The forest was a place I accessed mainly through stories, starting with fairy tales, then the Robin Hood books I devoured, and later the books of Patricia Wrede and Gail Carson Levine. I obsessively rewatched Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods, and usually turned up at sleepovers with my worn-out VHS of the Broadway production. (Much of the adult humor went over my head.) What was it about the forest that fascinated me? What was it that frightened me out of exploring it myself?

Probably many of the same things that fascinate and frighten us all. Journeys into the forest are as old as storytelling itself. The forest holds a mystical sense of danger and opportunity. It has the ability to conceal unknown creatures within its depths to capture and transform us.

These fears are not entirely unfounded. The news is full of cautionary tales of people getting lost in the woods. They might lose the path and freeze when the sun goes down. Or maybe they encounter a venomous spider or snake. Not to mention bigger animals such as grizzly bears and mountain lions. And then there’s poison ivy!

When we enter the forest, we are entering nature’s domain. We are at the mercy of critters and plants that live there. The woods are their home, not ours.

When I moved to New Zealand as an adult, I married into a family of conservationists. Suddenly my holidays were filled with treks up mountains and daylong hikes. The thing that inspired me was how dutifully and respectfully they approached even a short walk. You bring clothes that will keep you warm if you get lost. You never go on long walks alone, and always let someone know where you’re going and when you expect to return. You stay on the path to avoid trampling plants or the homes of animals. You leave nothing behind, and take nothing with you. People who ignore these practices are regarded as reckless amateurs, not brave adventurers.

One morning while out camping, I woke to see a wētā clinging to the fabric of my tent. My first instinct was to scream. I don’t do well with insects, and wētā are enormous, bird-sized crickets, named after the Māori god of ugly things. But a fellow camper excitedly led the wētā onto a stick and began to explain their incredible anatomy, their importance to New Zealand culture, and that some species are very endangered. I crept as near as I dared for a closer look. I still half wanted to scream, but a sense of wonder also started to bubble up inside me.

Once you respect the forest as a wild place, you can fully appreciate its beauty (even when it seems ugly at first glance). And once you understand its dangers, you can also see its fragility. How an act as simple as not washing your shoes can have disastrous effects if you track soil or algae to places they don’t belong. In New Zealand, the introduction of rats and weasels when humans arrived led to native birds competing for food and entire species being driven to near extinction. We humans have an extraordinary power over nature that should not be taken lightly, just as it has extraordinary power over us.

This relationship, the power that nature can wield and the respect we should show it, is a theme I have always explored in my writing and is central to A Wolf for a Spell. The villagers fear the forest because of its mystery and danger (and perhaps a witch or two), but the animals also fear humans because of their traps and weapons. Instead of caring for the forest and enjoying the benefits it offers, the humans let their fear lead to destruction.

Our own forests are every bit as magical as the forest inhabited by Baba Yaga, and as in need of protection. In writing A Wolf for a Spell, I wanted to dare readers to enter a world of danger and adventure and to leave with a greater awe and respect for the natural world around them, inspired to fight for its preservation.